Topography

What follows is a dialogue between Hoss Haley and sculptor/jeweler Susie Ganch. Susie is an associate professor in the craft/material studies department at Virginia Commonwealth University. In 2000, Susie and Hoss had adjacent studios as part of the Penland Resident Artist Program, and they have been friends, artistic colleagues, and interlocutors ever since. They spent several hours at Hoss’s house and studio in Western North Carolina talking about the sculptures and paintings that make up this exhibition. This is an excerpt from that conversation.

SG: Let’s talk about the sculptures a bit. You are using a repeating unit that is a semi-organic, semi-geometric shape. How did you arrive at that?

HH: These sculptures were based on small maquettes made from solid, forged elements. I started with round steel stock and forged it into rectilinear shapes with the purpose of letting all the ends squish out. In the translation from maquettes to sculptures, I wasn’t so interested in trying to convince anyone that the pieces are solid objects—they’re clearly not—but I wanted to use the visual language from the forged forms because it introduced an organic element, a softer form. It also allowed me to let go of some control and respond to what the material would do.

So, when you look at the sculptures, the curves were determined by the forging process and therefore are often asymmetrical and somewhat unpredictable. By approaching form development in this manner, a certain wabi-sabi effect can be achieved without it feeling contrived. Working this way feels more collaborative, and less like I’m controlling every aspect of what’s going on.

SG: After all these years of working, you have intuitive specificity that allows you to understand the ratios of measurement that appeal to your eye, but you’re also collaborating with the process.

HH: One of the reasons I chose to go back to forging—a process I used a lot many years ago—was that it’s highly reliant on trusting the eye. When forging, I really need to be able to see a right angle, to be able to visually track the movement of the metal. So with this body of work, I put down the tape measure and put the trust in my eyes.

What I like about these sculptures is that they reference the physical action of applying great pressure to something very solid. Steel can be very plastic, and the result of applying force to it creates a natural bulging as energy moves from inside to out. And then the rounded angles that are formed also read as erosion to me. In theory, if I put that same rectilinear steel bar stock out in nature, if it sat for eons, the corners would wear away, and we would see a similar effect. In this way, I’m thinking about time, too.

SG: Time is interesting to think about here. The way you’re using these multiple repetitive elements suggests cell division or growth. But then the way you’ve rounded the forms and rusted the surfaces suggests the opposite. I see them as suggesting both growth and decay at once.

You are actually translating our understanding of building through making, but then you are suggesting the erosive processes that are always at work on surfaces. Also, you have chosen this material, steel, and you are allowing it to rust. In a sense, you are suggesting time running in two directions simultaneously.

HH: Seeing it as time running in two directions is interesting. I guess I see it, maybe, more as cyclical: that as soon as it’s made it begins to rust, to go back to the earth, and at the same time, it could easily be reclaimed or re-melted and become something else. Either way my involvement is a brief moment in the life of the material.

SG: As I’m sitting here looking at your work, I can’t help but see your sculptures as pixels. They are square pixels of space. It helps me realize how informed you are by your upbringing in Kansas, growing up on the parcel of land that you farmed with your family. This work is a direct translation of who you are and where you came from.

HH: I grew up having a very visceral understanding of what a square mile was, because I plowed every inch of it. We had fields that were basically a square mile. And each square mile was part of a larger section. Farms in that part of the country are usually defined by sections.

Farmers organize the fields into neat straight rows, but in a relatively short period of time, nature would have reclaimed the land, erasing those lines. Spending hours and hours on the land, even as a young person, I thought about that push-pull. The whole idea that these sculptures are rectilinear shapes that essentially have had their corners knocked off is a response to the natural world having its own idea of order.

SG: It’s almost like you’re leaving room for nature to say, “No, squares don’t work in my world.” Certainly, we have to live in nature’s world.

How important is it to you that your audience understands the process behind these pieces? How informed does the viewer need to be about the type of manipulation required to make the steel do what it’s doing? How much do you leave for your audience to discover, and how much do you wish they understood that this work was informed by forging solid stock and translating those shapes into hollow forms of sheet steel?

HH: On the one hand, the process is everything for me. It’s all process. Process informs the work and is very important. But that isn’t the dominant aspect of the work that the viewer will experience. I do, however, try to present characteristics of steel that are not typically associated with the material. We tend to think of steel as being cold, hard, and unyielding, but it can also be the exact opposite.

SG: It’s almost like you’re playing a game of “what if” in your studio.

HH: It’s always “what if.” Every day is “what if.”

SG: That to me is a really interesting way of working because it’s about curiosity, problem- solving, and pragmatism. Everything about you is wrapped up in the decisions you’re making for the next move.

HH: I guess in that sense, I am not only the maker, I’m also the audience. I enjoy seeing what happens at each stage. That’s why I like the shifts and changes I make in the studio. For instance, when I move to the two-dimensional work, it’s another chance to respond to the three-dimensional work and say, how can I translate this another way? How can I keep exploring?

SG: I appreciate that you have an impulse to see the discoveries personally. And the rest of us get to enjoy your decisions, which I really like.

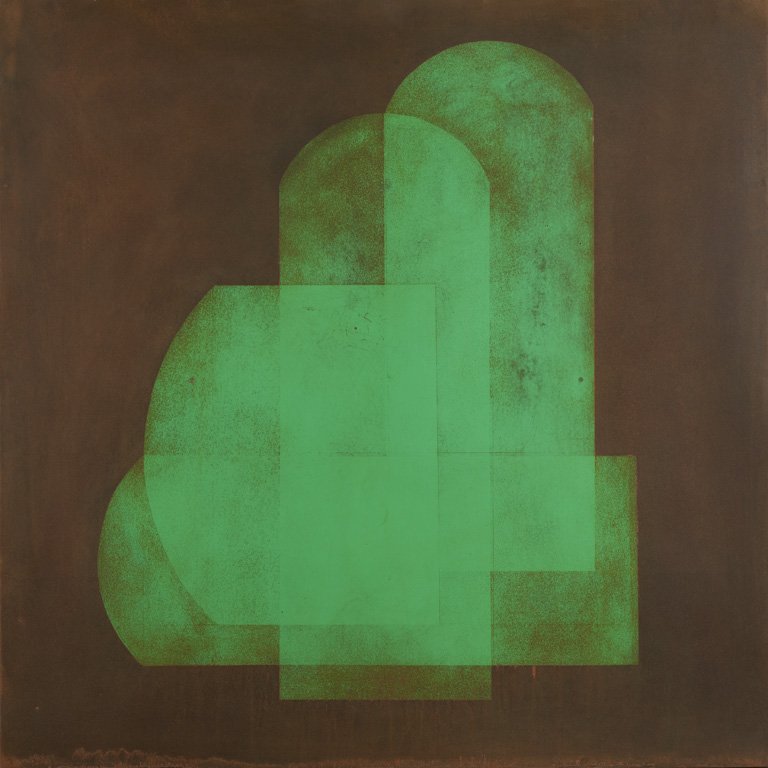

There is so much transformation from the three-dimensional sculptures in this body of work to the two-dimensional paintings that accompany them. You were able to give the planes dimensionality by editing information, layering flat planes on top of each other, and using transparency. The information you took away is importantly absent.

HH: My idea was to respond to the sculpture two-dimensionally: not to reproduce them, but to reinterpret them.

SG: Is there a faint horizon line appearing in some of the paintings? Did you create that or was that already on the surface of the steel?

HH: I made these paintings on pieces of steel that were originally one 24-foot painting. I cut that painting down and reused it for this series. So that line is leftover information, and that history is embedded in these six paintings.

SG: I love that mark. You are including the history of this repurposed material, which adds another layer of context and meaning. Is that something you were thinking about when you made these panels?

HH: Yes, that history is physically in there. I sanded down the panels completely, but because that horizon was created by rust, it’s actually etched in the surface. It is a slight dimensional shift in the surface of the steel.

SG: Speaking of dimensional shifts, the forms or planes in your paintings kind of float in a different universe. Do you see them that way? Ungrounded?

HH: It’s funny that you bring up floating because I think that faint horizon line grounds them for me. I have a really hard time not having that presence in the pieces. I think that just goes back to growing up in a place where the horizon is so prevalent. Everything is above or below a very clear division of planes. It’s a constant that I always knew or was aware of.

SG: Yeah. Big sky and land. Now that you live on the East Coast in the mountains, surrounded by trees, do you feel hemmed in when you can’t see the horizon? Does that influence your work? You don’t live with or have an awareness of the horizon in the same way here. Do you think about that?

HH: I think about that all the time! My entire makeup is based on those vistas, that horizon, from Kansas. It’s so ingrained in me that I don’t have to see it every day. I don’t have to be in it because it’s already part of me and what I make. Living here, the horizon is obscured by trees and mountains, years of growth and erosion. Again, that cycle of time. Totally different but in some ways the same.

Susie Ganch

Head of metals in Department of Craft and Material Studies

Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond); metalsmith/sculptor

Susie Ganch is a first-generation American artist of Hungarian heritage. She is a sculptor, jeweler, and educator living in Richmond, VA where she is Interim Chair for the Department of Craft/Material Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ganch received her MFA from University of Wisconsin-Madison. Part of her practice is Directing Radical Jewelry Makeover, an international jewelry mining and recycling project that continues to travel across the country and abroad. Issues of waste and cultural habits of consumption are imbued through her work.